Worth a thousand words

brot.dev is a image laden website. png’s are used in technical articles to preserve text in screenshots, while photos are better suited to be saved in jpegs. These two image formats are the behemoth web standards, serving us since the 90s. PNG dates back to 19951 (Did you know it’s supposed to be pronounced PING?), and JPEG goes back to 19922. Serving images is costly, often the largest contributor to a website’s size. Images are expensive for the website owner: storing the images on disk, bandwidth costs, and for the user: in time spent waiting for images to travel over the network.

There are newer image formats that can be used on the web, we don’t need to rely on the formats created in the 1990’s. Let’s dive into what new options are out there, what future developments are on the horizon, and how we can speed up brot.dev.

Let’s Talk About JPEG

JPEG stands for Joint Photographic Experts Group, and has become the defacto image format for photos on the web and our devices. JPEGs have amazing compression performance, are supported everywhere, and are royalty free. It’s important to know that JPEG is a codec and not a format. JPEG being a codec means you’ll find JPEGs contained in several file types, including embedded in RAW files (as previews), included in TIFF files (which are containers), and even formats like PDFs and MP4s (thumbnails). We’ll discuss more about codecs and formats later.

The main issue with JPEGs is that they can be quite large. While they achieve high compression ratios compared to formats like Bitmap (BMP), imaging science has come a long way in the past 3 decades. The standard library for making them—libjpeg-turbo—has a plethora of settings to choose from, stuff like chroma subsampling, quantization tables, progressive vs baseline images, etc. These are all great options for lowering the file size, but they can negatively impact the visual fidelity of the end image. We’ve come a long way since 1992, there are newer formats that offer lower file sizes while maintaining excellent image quality.

Enter WebP, JPEGXL, AVIF, and HEIC

You can find the list of commonly supported formats on the Mozilla Developer Network. The newest web friendly formats are WebP, AVIF and JPEGXL. Every single one of these has Google behind them in some form or another. Strangely enough, JPEGXL is being developed by Engineers at Google, supported in MacOS, and has been added and removed in Chrome. There’s also HEIC—another new format basically only supported by Apple. You can find support for HEIC in a decent amount of software—some hardware devices like Canon cameras can even output HEICs natively—but there’s no real push to increase adoption, and unless you only serve traffic to Apple devices, I wouldn’t recommend bothering with the format.

WebP isn’t good (for me)

WebP : is based on the VP8 video format and is very well supported on the Web, and natively on almost every device.3 WebP was introduced back in 2010, finding moderate success online. It does offer compression benefits over JPEG and PNG, but doesn’t support ICC profiles outside of sRGB. Because I like to save images in Display-P34 (Apple’s default color space), this eliminated it from the running for me. If you use alternate color spaces, make sure you correctly convert images to sRGB before converting to WebP.

Some other issues limit WebP’s usefulness. There’s been a push towards HDR images, which require 10 bits per channel, and WebP only supports 8. So if you’re starting a new project, it’s a good idea to look at other formats. Since these issues are fixed in AVIF there isn’t a good reason to pick WebP for this site.

HEIC, and what’s HEIF?

Apple introduced HEIC with iOS 11 in 2017, and Apple Devices have been supporting them since. It supports 10 bits of color information, and can support features like cropping while still storing the original image. HEIC enables the preview and source material to remain distinct in the same file. But with iOS 17 Apple confusingly mentioned that 48MP files are saved as HEIFS. Are these the same thing? To clear up any confusion let’s quickly break down the difference between HEIC and HEIF:

- HEIF: High Efficiency Image Format

- HEIC: High Efficiency Image Codec

HEIFs are the container that holds an image, which can be a HEIC. HEICs are compressed using HEVC, more commonly known as H.265. HEIC does offer good performance over JPEGs, but the codec HEVC requires a license. A license requires spending money, which is a hard pill to swallow when there are royalty-free options on the market. That’s probably why the codec never really took off for images.

Speaking of HEIF…

AVIF is actually a HEIF (as a container) using AV1 to encode the image!

AVIF is basically WebP 2.0

Much like the aforementioned WebP, AVIF is also based on a video codec: AV1. While I haven’t seen much discussion about AVIFs online, the format is supported by all modern browsers. It’s a version of WebP that offers increased compression performance, supports ICC profiles, and 10-bit colordepth. So I would rather just support AVIF and drop WebP for this site.

There are some other smaller issues that didn’t impact my decision, but are worth noting if you’re considering AVIF or a Video Based Format is that you can’t really download these images progressively like you can with a JPEG. It has something to do with the format functioning as basically a single frame of a video—I’m not sure. WebP has a similar problem.

Jake Archibald wrote at length about these formats and has lots of examples on his blog, which you can check out here. Jake dives into all the formats in a technical level if you’re interested in fun topics like palette reduction or chroma subsampling.

JPEGXL & Google’s Complicated Relationship with it

To steal a line from Wikipedia:

Google’s stance on JPEG XL is ambiguous, as it has contributed to the format but refrained from shipping an implementation of it in Chromium and Google Chrome.

You can find articles online discussing Google’s decision to remove support for JPEGXL despite staffing a team to contribute directly to the format5.

But I like it! It’s a free and open source format, it’s being actively developed, and Apple’s pushing support for it. Starting in MacOS 14 and iOS 17 back in 2023, and now ProRAW on the iPhone 16 pro also supports JPEGXL! This is a big step in the right direction and hopefully a move away from their use of the license-restricted HEIC. There’s news that Firefox will consider a Rust implementation of JPEG-XL, the decoder ironically being built by a team at Google.

How I prepare files for brot.dev: Brot-Baker

I created a small script in Go that takes my directory of JPEGs and outputs AVIFs and JPEGXLs of all the images. I call it brot-baker, since it keeps with the bread theme. It’s written in Go because I originally wanted to work directly with the Image Package, but I quickly ran into limitations with how it handled details like ICC profiles (It doesn’t).

The reference libraries for JPEGXL and AVIF are all C libraries. With no native Go support, brot-baker became a script, as you still need to have the underlying C libraries installed on your system.

I’d like to come up with a way to incorporate directly with hugo, which is the static site generator I used to build this website. Need to explore a native integration that keeps the JPEGs separate from the JPEGXL and AVIFs, so that it’ll be easier to add and remove images as I’m working on a post.

The golden <figure> snippet

I use an edited <figure> shortcode that you can find on brot-theme here. The shortcode takes advantage of the built-in capability of the <picture> element, which can have multiple sources included and the browser will pick the first one it supports. Read about it on the Mozilla Developer Network.

Chasing Smaller Sizes in vanilla JPEG

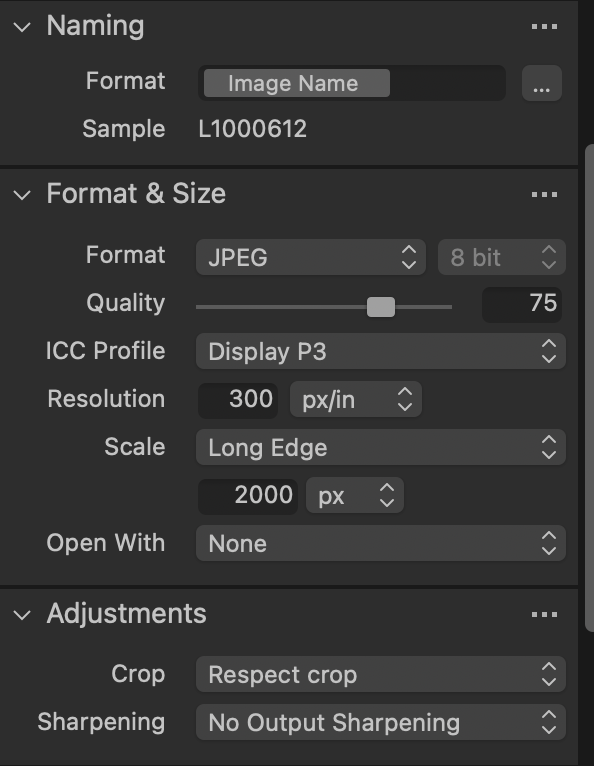

When setting JPEG settings in Capture One, I used the following settings until the Summer2024 post:

Sometimes I switch sharpening on or off. I like to crop and sometimes sharpening on crops gives weird results

This would produce JPEGs that tended to be rather large, and vary in size from ~400KB to well over 1.5MB. There was another website that I like to visit— gear.vogelius.se— where the images would be 700KB or lower and still maintain great image quality. Even though I don’t pay hosting costs, performance still suffers from the large file sizes. And in case I ever need to switch hosting providers, having small images already available will make the transition less painful.

MozJPEG to the rescue!

Exploring some JPEG optimization guides online, I stumbled upon two JPEG encoders that produce better compression ratios than the standard libjpeg-turbo.

- MozJPEG: A patch for

libjpeg-turbowith a focus on higher visual quality at smaller file sizes at the expense of encoding speed. - Jpegli: A jpeg encoder that spun out of the research done at the JPEGXL project!

At the time of writing, there was no straightforward way to use jpegli. There are no binary downloads for MacOS, and I didn’t want to faff around and download a massive codebase with an annoying build system, or install docker. I decided to go with MozJPEG.

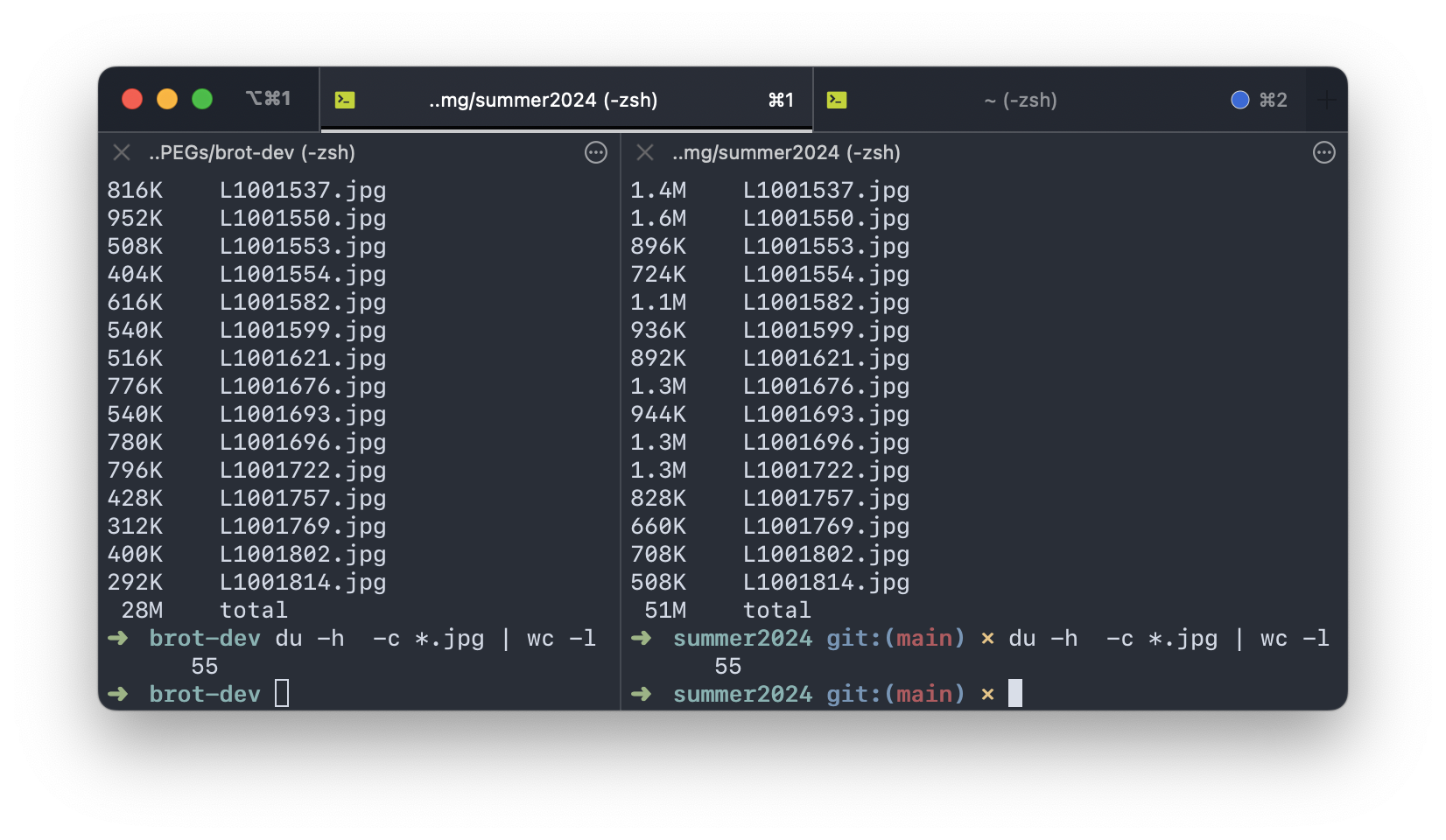

I ran MozJPEG against the images in my Summer2024 post, check out the results:

The original libjpeg-turbo jpegs are produced directly from the RAW files in Capture One. The MozJPEG jpegs are produced by exporting the RAW files as lossless PNGs and then converting them using cjpeg. cjpeg is utility installed as part of the MozJPEG package, allowing you to convert to jpeg from a lossless image format like BMP or PNG and outputs a JPEG.

The MozJPEG jpegs are set at quality setting 80, and are ~55% the size of their respective libjpeg-turbo brethren at 70%! This was all the testing I needed to see that it was worth switching. Some tweaking was needed to the get the outputs looking as close as I could.

Testing to see what the new JpegXL and AVIFs look like

Because the JPEGs are smaller and use different encoding methods than vanilla libjpeg-turbo, I wondered if size savings would translate to smaller file sizes in the AVIF & JPEGXL conversions too! Let’s see:

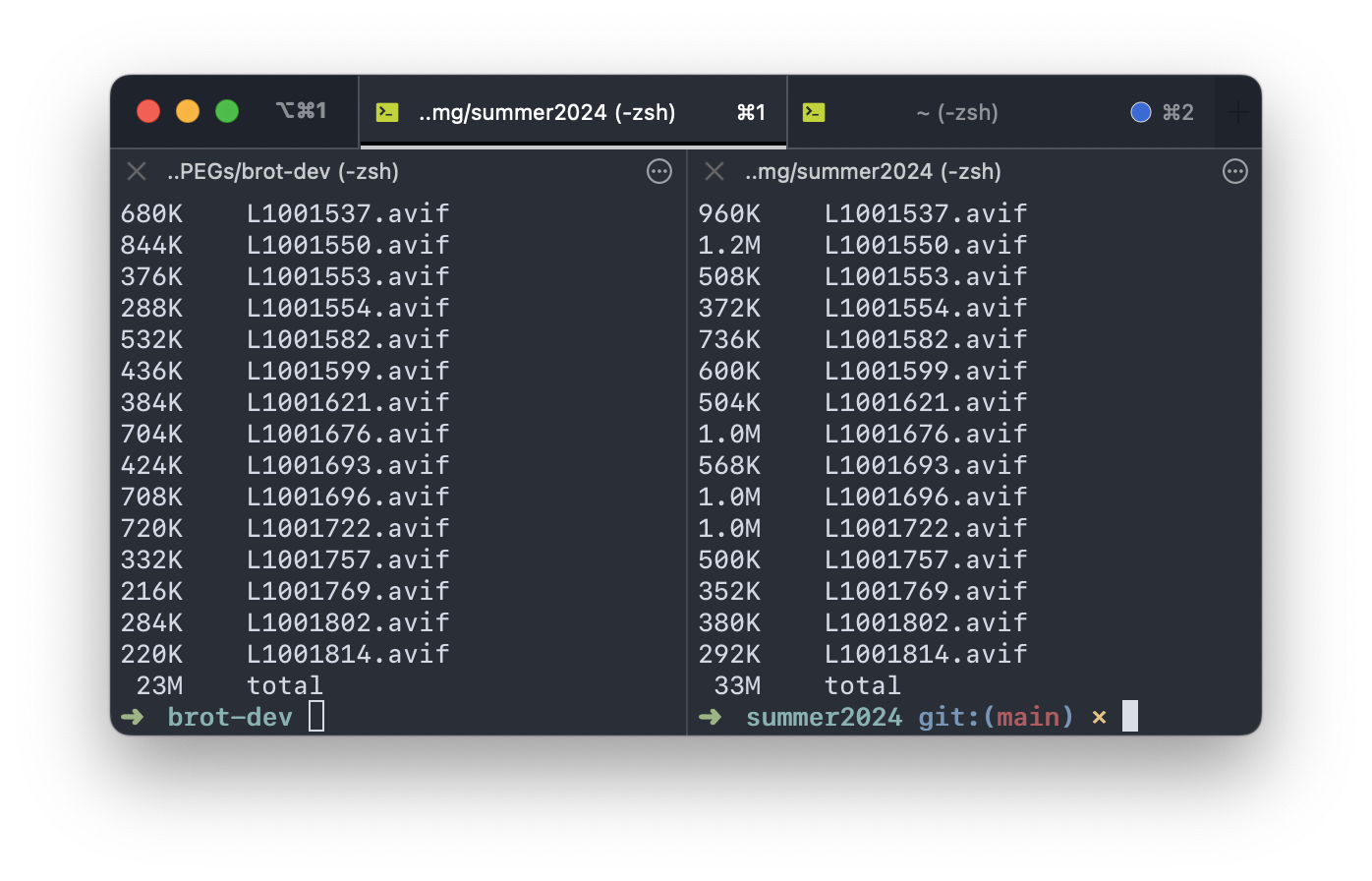

AVIFs

Around 70% smaller. Nice. AVIFs will have the worse image quality because they’re processed from already-lossy JPEGs. If you ever want to see the original JPG’s that they’re derived from, you can view the sources on this website via Dev Tools and it’ll show you all three options of any image in the source code. Hint: they’ll be in the <picture> elements. You can also right click, open image in a new tab and change the extension to what you prefer.

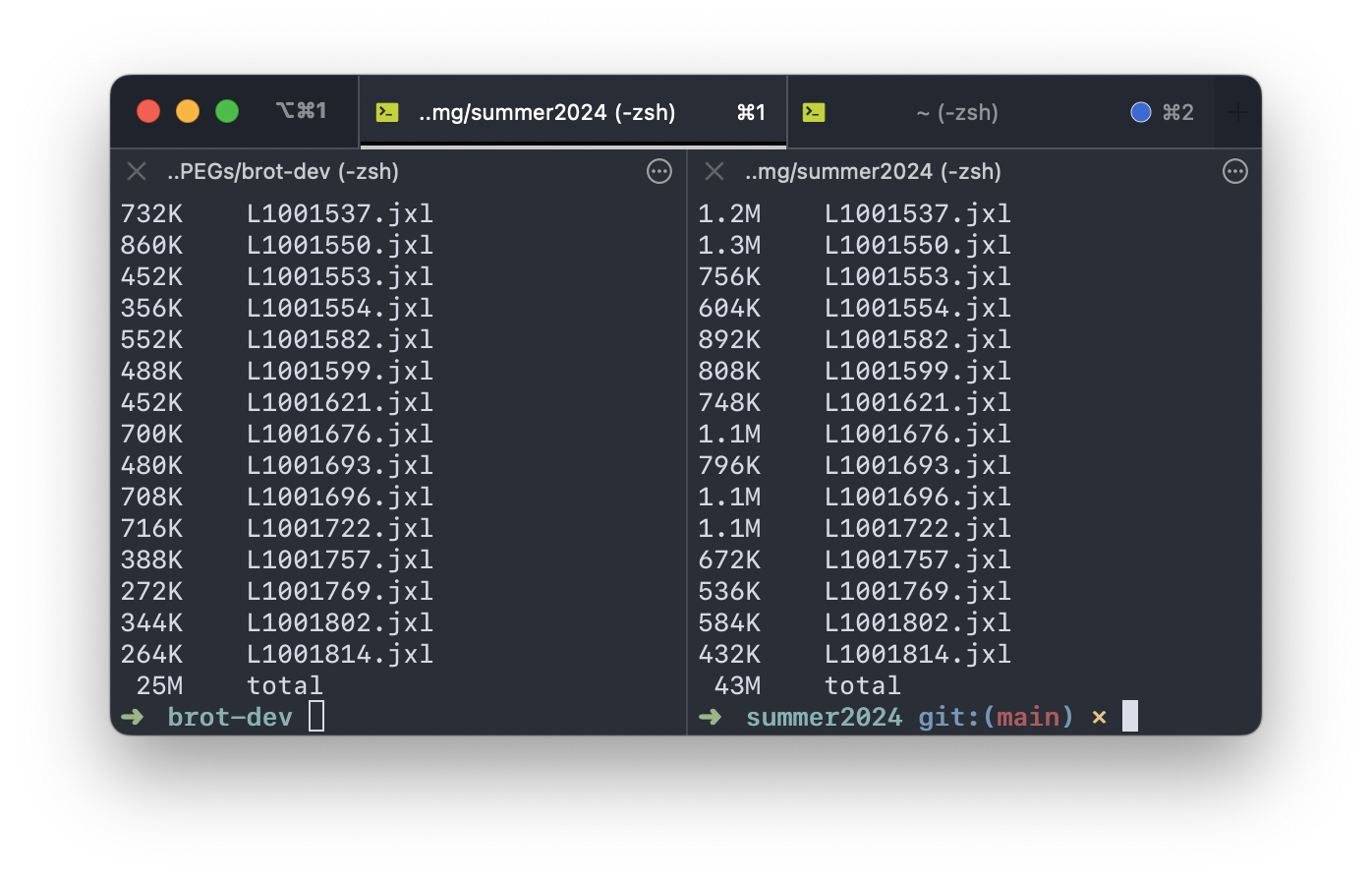

JPEGXL

The MOZJPEG-JXL versions are around 58% of their LIBTURBO-JXL counterparts. So we see some size savings! Importantly, these .JXL’s are processed using JPEGXL’s transcoding feature, which means that you get the benefits of additional compression but without any additional fidelity loss. You can revert these JPEGXL images right back to their original JPEG! Sweet!

Right for me, but what about you?

I chose to use AVIFs and JXLs on my site, but I serve basically no real-world traffic, and don’t have to worry about legacy support. This article ignores other important formats like SVGs or GIFs, which require their own solutions (But both can be encoded with AVIF OR JPEGXL6!). For even more resources about how to pick image formats for your site, Cloudinary has a great guide to help you figure out what’ll work best for your use case!

https://webkit.org/blog/10042/wide-gamut-color-in-css-with-display-p3/ ↩︎

Caveats here: animated AVIFs only in some browsers, same with JPEGXL. ↩︎