What is cybersecurity?

Simply put: cyber security is about maintaining the confidentiality, integrity and availability of information. In practice, it’s about finding the right balance of balancing everything I just mentioned with budgets, user experience, and developer experience. Infosec, security engineering, enterprise security— are all terms used to refer to the field.

Some people spend all day writing IAM roles on AWS, others will be reversing binaries, and others will be responding to cross site scripting reports that come in through a bug bounty program. From the high-level protections like setting password policies to protecting against side-chain attacks by reading CPU temperatures someone’s out there doing it.

This article will focus on my experience as a Security Engineer, rather than as an analyst, or a researcher. I’ll touch briefly on those roles in this document, but won’t focus on them.

How to get into the field

I just have a lot of pictures of Duo around so I’m dumping them all into this article

Building your skillset

Getting your foot in the door is really the toughest part. In order to prepare, you’ll need to follow at least two of these 3 paths:

- Get a college degree in Comp Sci, Cybersecurity, or some Software Engineering-esque field

- Work on side projects, write blogs, teach others, just build things.

- Study for certifications

Getting a college degree is valuable because there are many firms who hire positions specifically targeting new grads & interns. Both of these positions are unavailable to those who’ve been part of the field or who are attempting a mid-career switch, so it’s important that if you’re in a position where you can take advantage of these opportunities that you plan ahead of time. New grad/Intern positions can be filled by the October or November the fall before the jobs even start, so you need to plan far in advance. Bootcamps exist, but the harsh reality is that I often see bootcamp graduates struggle to fill these roles. The quality of bootcamps vary so wildly that certain hiring managers choose to not take the risk of hiring those individuals.

You don’t need to publish these projects or put them on GitHub. You can just find things that you’re interested in and work on those. Even projects that aren’t security related can prove very useful. Learning what things you’re not interested can be equally as important than finding things you are interested in. That’s one of the best parts of an internship—it gives you 2 or 3 months to try something brand new, and if you don’t like it, do something different the next summer.

Writing a blog and teaching others is a great way to think critically about things you know. Teaching a class, or offering to TA in some capacity gets you to understand a topic on a deeper level, and can be great experience for mentoring junior engineers later on.

The studying done in order to get a certification is more important than the cert itself. Practice tests are a great resource to test your own knowledge and can be really good prep for technical interviews. The cert itself can also help get you through screenings if a hiring manager has a particular certificate in mind, and is usually in the ’nice to have’ section of job postings. Sometimes the cert doesn’t even need to be security related. It could be that a hiring manager is looking for someone with management experience. But for cert recommendations, see this section on which ones I recommend

Getting ready for interviews

Once your application makes it through initial screening, you’ll typically have some intro conversation with the recruiter. This first interview is to screen whether or not you’re human, and feels more like a gentle ‘vibe check’ to see if you’d be a good cultural fit.

Interviews typically follow a standard amount of 3-5 rounds, where there can be 1 or more panels where you’ll see questions that fall into one of these larger categories

- System Design:

- This could be a DevOps-style question where you’ll have to talk about setting up a new VPC or the infrastructure for an app to use. It’s important to demonstrate you know how networking works, the difference between private & public subnets, and it’ll show if you’ve worked with application gateways and how databases deployed in the cloud or on-prem.

- These interviews may include terraform, but not typically for new-grad roles. If this is given to you be prepared to look at bad terraform code and explain how you’d fix it. In this context bad terrform could be bad as in style—not using modules, hardcoded values—or bad as in security—EC2 instances without security groups, public ACLs on S3 buckets.

- Security Questions:

- These will typically be surface level questions about academic security topics like explaining with XSS scripting is or the difference between asymmetric and symmetric encryption algorithms.

- I suggest looking closely at the OWASP top 10 cheatsheet and getting familiar with the terms and how to explain them.

- These will typically be surface level questions about academic security topics like explaining with XSS scripting is or the difference between asymmetric and symmetric encryption algorithms.

- General Coding

- This will be the same (or easier) than the coding interview questions a Software Engineer would normally get. Think puzzles and algorithms. I suggest doing them in Python.

- Hiring/Role Manager Meeting

- This would be your future boss. You should be asking important questions like what the daily operations look like, perks, vacation policies, management style here.

- Team Meetings

- You’ll meet with the team, different from the hiring manager since these people tend to answer questions regarding things like daily operations and work-life balance more earnestly.

- Salary/Equity/Total Comp conversations

⚠️Important to remember⚠️ You should ask your recruiter questions about the type of interviews that are up ahead—as well as the materials previous successful candidates used to get offers. This will help you identify which parts of the process you should be spending the most amount of time studying.

Example: I got these notes from my recruiter when interviewing at Google, and it was good prep for the upcoming rounds of interviews.

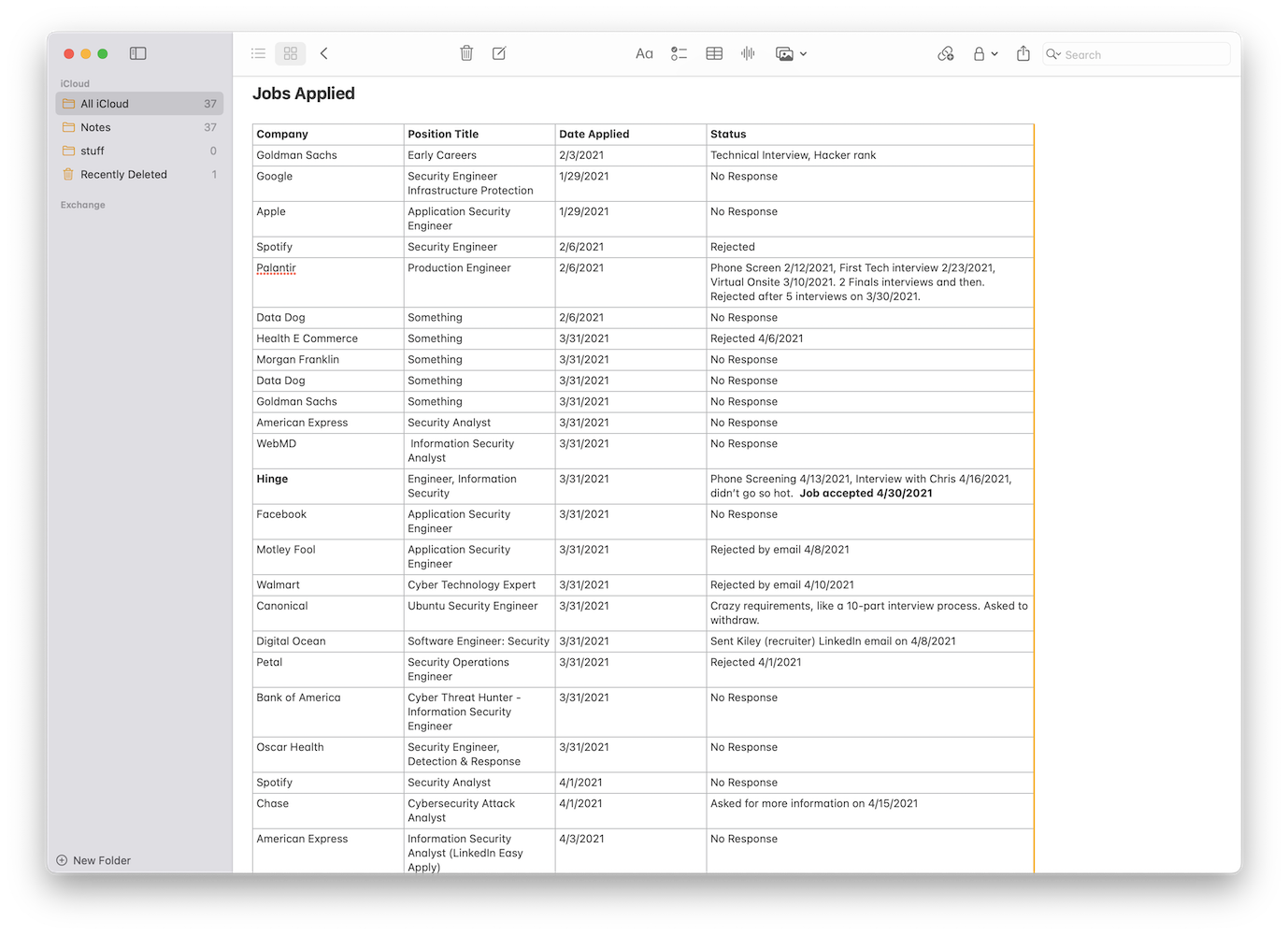

Rejections and ghosting

This isn’t unique to Security Engineering, but ghosting and rejections are quite common in the job market, regardless of if it’s in tech or not. In my experience I heard back from maybe 10% of the places I sent a job application to. Sometimes I’d get a rejection email 6 months into working my new position, or I’d get a recruiter sending me emails the week I started a new job! You really just have to get used to the grind of sending our your resume, keeping it up to date, and setting alerts on job sites for companies you’re interested in working for.

My partial list of jobs I applied to during my search for my second position.

Referrals are great, but not necessary

I only ever had a referral for one job that I ended up getting: MITRE. The other two jobs I’ve gotten were jobs I found on LinkedIn and applied directly on the company’s career page. You don’t need a referral to get a job, but there are plenty of people giving them out. At larger firms, you can check Blind to see if anyone will give you one. As you progress in your career, it’ll be easier to pick up referrals, which is why it’s so important to always think about how you’re building your professional network.

Public versus Private Sector

The missions are very different between Private and Public sector positions, and things like salary and benefits vary wildly. When I worked in the public sector, I was required to be in the office 5 days a week, there was no free lunch, and my total compensation was half of what it would’ve been in the private sector. But I could really go heads down in security work. There are concerns for costs, but the public sector doesn’t really bring in ‘profit’ the way a private company does, and you can work on really interesting research. Defense budgets are incredibly bloated, so there’s room to take big swings or work on very technical stuff. You won’t be able to talk about it with friends or family, but it could be highly rewarding work.

In the public sector, the money’s in getting a security clearance. This means no drugs for anywhere between 1-3 years depending on the agency you’re applying with. Even if you’re aiming to work at a contractor like Lockheed Martin or Palantir, you’re going to want to get a Security Clearance. Those positions generally pay better, the work is more interesting, and you give yourself job security.

The private sector offers more flexibility. You can find remote work if you’re interested—but I generally would recommend newcomers to any field to not work entirely remote. Your total compensation can include equity and bonuses on top of your regular salary, and you could get generous PTO. But outside of a giant firm like Google or Meta, and firms that just do security things like HUMAN or Wiz, you won’t find a ton of research opportunities.

How Security functions as part of a larger organization

Working at a product driven organization is very different from working in a Government position or Security firm. Security takes a backseat to the product, as that’s what drives the revenue and ultimately pays your salary. At MITRE, security was paramount, a lot of time was spent making sure things were carried out in the proper fashion. We had laws we needed to follow since we were contracting for the government, and when working on sensitive information, a failure in security could compromise a project, or even endanger someone’s life.

At Hinge, building the product and increasing user count was #1. We had shareholders as part of a public company, and Hinge is owned by a parent company, which means there was always pressure to bring in more money and drive the stock’s performance. Security mattered to the degree that a lapse in security could draw bad press to the company.

My Background - And thoughts on company sizes

I’ve been doing Security Engineering full time since 2019, graduating RIT with a bachelors in Cyber Security with a double major in Economics. I went on to get my start at MITRE as a cybersecurity engineer and then went on to do security engineering at Hinge before ending up at my current position at Duolingo.

I did two summers of internships for the Department of Justice before starting fulltime work. Before that that I did some administrative office work just to get some cash to pay for school. Now I’m a Security Engineer for Duolingo, doing Cloud and Application security.

MITRE

MITRE is a nonprofit dual-headquartered in Bedford, Massachusetts and McLean, Virginia. I worked out of the McLean site as what’s sometimes referred to as a “Forward Deployed Engineer”. This meant I worked at sponsor (MITRE’s term for customers) site, rather than at a MITRE office. In this case that meant working at the Department of Justice, helping assist special agents with cybersecurity issues.

As a company with over 8,000 employees, it’s a great place for a junior engineer. There’s a lot of senior+ talent that you can learn from. And MITRE was spread out across multiple areas of the government, and created some very famous security products. The MITRE ATT&CK Framework, CVEs, CALDERA are all things MITRE created. (I didn’t work on any of these)

Hinge

Hinge is a dating app company owned by MatchGroup. Instead of 8000 employees, there were ~150 at the time I started. I was the first hire of the security team they were planning to build out. With no senior engineer to mentor me, and still being quite junior in my career meant that there were many times where people asked me questions I did not know the answers to.

A much smaller company and an insanely lean team does come with one really large benefit: You get to do everything. If you want to mess around with VPN configurations, AWS security groups, set up a SIEM, or install some CNAPP tooling… you can do it—budget allowing.

I felt I was unqualified when I took this position. I applied having met only the basic requirements and with not much experience running anything enterprise. At MITRE my focus was more on security software engineering, and at MITRE it was more enterprise security engineering.

Duolingo

A larger security team with a dedicated manager and several people on the team, it was still by enterprise teams lean.

This is great for many the same reasons as small teams on Hinge was. But Duolingo was a much more established company at this point, so this presented some interesting challenges. Like taking what was built by a previous security team and evaluating the decisions that were right at their size, and wondering how to scale as our user base and employee count grew.

I’ll talk more about my work at Duolingo some other time. There are lots of projects in flight and fun stories to get into. But it’ll have to wait for now!

FAQs:

Do I need side projects on my resume?

It depends on the company you’re interviewing for. When I applied to Google for a Security Engineering role, they asked specifically for projects on their application, but that is the only time I’ve seen that. That was the only role I can remember where I was specifically asked for some side projects. At the time I didn’t have much on my GitHub, so I uploaded some course work from college.

It’s “a nice to have”, but in my experience giving interviews, it hasn’t come up as a deciding factor.

What are all these positions like blue team and read team? SOC? Cloud Security? Reverse Engineering?

Let’s briefly get into the bigger specialties in security, and what they do.

Blue Team

The most abundant “Security Engineering” role is going to be some sort of Blue Team position. In Security Engineering, “Blue Team” means you’re tasked with defending company assets like

- Systems

- Could range from AWS EC2 instances (Virtual Machines), or Data Centers with bare-metal servers.

- Networks

- These are the systems that devices communicate over. If the company has a VPN, it would mean managing that, along with protecting and monitoring internal networks and private sites.

- Data

- Client Data

- Purchase History, PII (Personally identifiable information), Duolingo Streak length.

- Employee Data

- Compensation Data, Tax information, Addresses, Phone Numbers, etc.

- Client Data

Red Team

This is the attack counterpart to blue team, where the goal is to break into systems and networks to see what kind of information could be gathered. Sometimes called “penetration testing”, many smaller companies will hire a security firm to run these sorts of attacks against their infrastructure to see what vulnerabilities they have that their blue teams haven’t caught or thought of. Larger firms sometimes hire their red teams internally or will do a mix of external and internal.

SOC (Security Operation Center)

SOCs detect, monitor and analyze threats. They’ll do this by monitoring the data gathered by tools like EDR, SIEMs, IDPs/IDPs. They’re a 24/7 operation which is setup to respond to incidents. A SOC is either internal to the company, or it will be outsourced. If you see the term MSSP— That’s a Managed Security Service Provider.

Since a SOC is 24/7, there are multiple shifts to cover, and there’s weekend work available. You can be a Security Engineer, Security Analyst, work in Compliance, or be a Manager and work as part of a SOC.

Reverse Engineering + Research

This specialty is all about understanding software and how it works. Going through a decompiler like Ghidra or IDA Pro. Groups like Google’s Project Zero are famous for finding flaws in software like discovering exploits in iPhone’s via iMessage, Google’s Chrome browser, and authentication bypasses in Hashicorp Vault. They also write some stellar blogposts of how they find these issues and how they can be exploited.

What does a day in the life of a Security Engineer look like?

The typical day starts with some sort of standup, where you’ll update team members about any work you’re currently taking care of, or starting that day. If you’re on a type of rotation, that might involve seeing what requests engineers have put in (e.g. Asking for a Code Review, or security feedback on a Design Spec ).

How much programming do I need to know?

For Security Analyst positions, you don’t need to know much— or any programming. For any job title with “Engineering” in the title, you’ll need to at least know some programming for the interview process. Typically Security Engineering interviews don’t involve as many programming panels as regular Software Engineering positions, but I would expect at least one.

I haven’t gotten questions for Security Engineering interviews that were the typical “Leetcode Hard” that you’d get in a Meta (The company) interview. They were all typically data-structure based, seeing if you know concepts like O(n) time complexity and how to write some basic algorithms.

If you haven’t already, I recommend knowing some Python. It’s the language that most engineers will at least know how to read, so you can usually pick it for any coding panel you would have.

How do you deal with imposter syndrome?

There’s so much to know in the realm of Security Engineering, no matter what specialty you’re trying to get into. There are some incredibly talented people in the field, so-called ‘cracked’ engineers. People who learned how to jailbreak iPhones before they turned 18 (ala George Hotz), it can seem like there’s no way I could enter this field.

You’re not going to know even half of your specialty by the time you get started, and that’s okay. You’re gonna stumble across issues you’ve never seen before in codebases you’re looking at for the first time. People are going to ask if something they’re working on is following best practices and you won’t know the answer. It’s going to be alright. You’ll learn.

If you’re starting off, you should be on a team where you have senior employees (or a manager) that can help point you in the right direction. No one is going to know the answer every time. Do your research, check what OWASP says about the issue, or ask ChatGPT.

It’ll get easier, but you’ll never know everything. You’ll find a rhythm, learn how to teach yourself quickly, and how to tackle unfamiliar situations.

Do I need a degree to get into the field?

You don’t need one, but it’ll help a lot. Some job postings, like new grad or internships, will often have a graduate requirement and won’t accept bootcamps. For public sector jobs, there’s typically a degree requirement. The degree doesn’t need to be a degree in cyber security, you can have one in any Computer Science related field. Without a degree, I would highly recommend getting at least one certification from a reputable provider. See the next section for certification recommendations.

Do you have any certification recommendations?

- CompTIA Security+ is one of the most popular and well respected certification in the field. It’s aimed at Early Career folks!

- CompTIA A+ is a more generic IT certification, which can be a good starting point before taking the Security+ exam.

- CISSP which is very common as well, but requires ‘5 years work experience’ before you can enroll for a test.

- SANS offers a lot of cyber security resources and certifications, but they’re very expensive to purchase as an individual.

- OSCP+ This is a certificate focused on penetration testing.

I didn’t get any of these certifications myself, but I had a bachelors in Cyber Security. Once you’re no longer entry-level, people don’t care as much about certifications1, but if you’re trying to build up your skills, the certifications I linked above are a good place to start.

Do you have any tips for what to include on a resume?

- If you’re linking a GitHub (or GitLab/Bitbucket) account, make sure it has something on there. Having a completely blank GitHub on a resume looks weird, it would better to use that space to talk about past accomplishments or just link to your LinkedIn instead.

- If you have some open source contributions, include those!

- If your GPA isn’t a 3.5 or above, leave it off your resume.

- If it’s on your resume, be prepared to answer questions about it. The interviewer may have a particular project in mind for you based on a point raised in your resume.

What questions should I ask in interviews?

- How big is the team?

- Are there senior staff that can mentor me?

- What’s the process for getting security issues fixed?

- Do we have to go to managers? Do I work directly with PMs to get issues assigned to engineers? How do we prioritize security work among other tasks?

- What’s the workload like?

- Is there a backlog that extends 3 years into the future? How’s the balance between ad-hoc work and project work?

- How is the success of a security engineer measured?

- When performance review cycles come, what does management consider a success? Is it finding issues, fixing issues, project work?

- Is there an on-call rotation? How big is it? Is it busy?

- Are engineers getting paged regularly on weekends? How often am I going to be on rotation? What are the SLAs? Are there rotations that aren’t on-call that I’ll be a part of?

Public Sector jobs sometimes ask for particular certifications, especially if you want to get higher on the GS pay scale. ↩︎